By Norm Stamper

By Norm Stamper

June 1, 2005

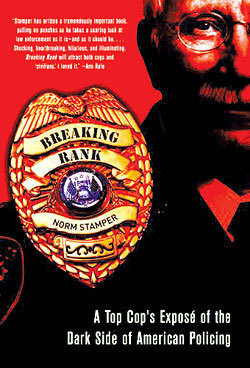

A Good Cop Wasted

The WTO debacle brought down Seattle Police Chief Norm

Stamper, one of America’s most progressive cops. Now he’s published a

memoir offering a frank look at his rise and fall, and the challenges

of reforming law enforcement. By Nina Shapiro MORE

"Snookered in Seattle: The WTO Riots" is a chapter from the

book Breaking Rank, copyright © 2005 by Norm Stamper, and appears by

permission of the publisher, Nation Books, a division of Avalon

Publishing Group Inc. The former Seattle Police chief will speak at

Town Hall Thurs., June 9, at 7:30 p.m., sponsored by Elliott Bay Book

Co.

I was "out of the loop" on the decision to invite the WTO

Ministerial Conference to Seattle (November 29-December 4, 1999). I’m

not sure how I would have voted anyway—for all I knew, "W-T-O" were the

call letters of a Cleveland radio station. I will say this, though:

Having your ass kicked so completely—by protestors, politicians, the

media, your own cops, colleagues from other agencies, and even a

(former) friend—does give cause for pause and reflection.

Local politicians were ecstatic that Seattle had beaten out San

Diego, the only other U.S. finalist for the honor of hosting the WTO

Conference. Our city of 530,000, with its police department of twelve

hundred cops, was delighted to accommodate eight thousand delegates,

the president of the United States, the secretary of state, dozens of

assorted other dignitaries, hundreds of reporters from throughout the

world, and tens of thousands of antiglobalization protesters.

No one was more tickled than Mayor Paul Schell. He wrote in an issue

of his "Schell Mail" A folksy missive from the mayor to thousands of

Seattleites, inside and outside government, issued as events dictated

or inspiration struck. His opponents accused the mayor of using "Schell

Mail" to advance a political agenda—particularly with respect to

mayoral dreams (including re-election), programs, and budget requests.

As one of his cabinet members, I found the Schell Mail messages

informative. (No. 39): "As the whole event comes to a peak during the

days of the actual Ministerial our streets and restaurants will be

filled with people from all over the world. Issues of global

significance will be addressed in our conference halls and public

spaces. School teachers will use local news to teach international

civics lessons. (And our many visitors will be bringing something like

$11 million of business to our town.)"

Schell had that very morning met with Michael Moore (no, not the

Michael Moore, but the secretary general of the WTO). He wrote of the

meeting, "Ex-Prime Minister of New Zealand, ex-construction worker,

with a background in labor, and an author, he’s got a good sense of

humor and a great mind. We had fun giving him a big round of ‚g-day,

mate.’" Then he turned serious: "Though there’s been a lot of talk

about protests and demonstrations, without question these are

overblown." Everyone (except us killjoys in law enforcement) seemed

unable to curb their enthusiasm about the event. Especially the

antiglobalization forces.

One city council member invited protesters from around the world to

come to Seattle to join in the "dialogue." He issued urgent public

appeals to Seattleites to find room in their homes to house the hordes.

Early in ’99, before pre-event speculation heated up, Ed Joiner, my

Operations chief, and I walked the few blocks down to the local FBI

office to learn what this WTO thing was all about from the "law

enforcement perspective." Special agent in charge "Birdie" Passanelli

and her fellow feds offered a primer. The World Trade Organization was

established in 1995 to "oversee rules of international trade, help

trade flow smoothly, settle trade disputes between governments, and

organize trade negotiations." Simple enough, I thought. An innocuous

mission with an emphasis on the bureaucratic and the diplomatic.

The WTO stood for the facilitation of free trade while its opponents

favored fair trade. "Free," "fair"—what the hell was the difference?

I boned up on the controversy. "Free trade," I came to understand,

means, essentially, the Clinton agenda—NAFTA, an opening of markets

throughout North America and, beyond that, the reduction or elimination

of trade barriers such as tariffs and quotas. Advocates claim that

global free trade would reduce poverty, encourage greater economic and

political freedom, increase corporate profits, and even enhance the

environment. The most succinct free-trade argument I found, invoking

Adam Smith, free enterprise, and the evils of socialism, came from

Milton Friedman and Rose Friedman in "The Case for Free Trade" (Hoover

Digest, 1997, No. 4).

In the view of its legions of disparate critics, however, free trade

means devastation of rain forests and other irreplaceable ecosystems;

loss of small American farms, businesses, and jobs to global

conglomerates, agribusiness, and foreign sweatshops; world hunger;

expansion of American imperialism; exploitation of laborers and the use

of child workers in Third World countries; political imprisonment; a

crushing subjugation of countries like Tibet; corrupt business

practices by the multinational corporations; abridgment of intellectual

properties; and denial of basic human and civil rights.

The last ministerial conference, in Geneva in May 1998, had

attracted thousands of demonstrators, and it had turned violent. But

President Clinton, a big supporter of the WTO, offered up the United

States anyway. He was probably thinking, No problem. I mean, how long

has it been since the country has seen violent political protest?

Twenty-five years? Thirty?

Seattle had handled, since the general strike of 1919 and through

the antiwar and civil rights uprisings of the sixties and seventies, an

unending stream of political demonstrations. Even in the mid-nineties

it was like the city was frozen in time—or, depending on your politics,

ahead of its time.

Seattle is a progressive town, one that can always muster several

hundred, or several thousand, to protest social service budget cuts or

police brutality or the conditions of migrant farm workers on the other

side of the Cascades. I felt privileged to live and work in a town

whose people still cared enough about social justice to get off their

butts and help bring it about.

We launched a regional planning effort on the heels of that FBI

meeting. Joiner headed up a "Public Safety Executive Committee"

consisting of ranking officials of SPD, King County Sheriffs, Seattle

Fire Department, Washington State Patrol, the FBI, and the United

States Secret Service. In all, twelve local, state, and federal

agencies plus sixteen collateral agencies joined the planning effort.

Joiner and his group formed subcommittees to address every

imaginable challenge: intelligence, venues protection, demonstration

management, access accreditation, transportation and escort management,

criminal investigations, communication, public information and media

relations, hazardous materials (including weapons of mass destruction),

fire and emergency medical services, tactics, logistics, personnel,

finance, and training.

Their mission? Put together a plan to protect people—conferees,

demonstrators, residents, business owners, shoppers, and dignitaries

(the secretary of state, the secretary of labor, the president himself,

maybe even Fidel Castro, who’d been rumored to be on the list of

uninvited but expected guests). And property—the streets, the

convention center, downtown hotels, Old Navy, Starbucks, Nordstrom,

Nike, the Gap, independent news and espresso stands …

My purpose as a cop, as a chief was to make our streets safe—for

everyone. When people asked me to describe the mission of SPD I gave

them a stock answer: to stop people from hurting other people. It

didn’t matter to me whether the danger was in a couple’s apartment in

Greenlake or on downtown streets jammed with demonstrators.

The police would, in the mayor’s words, "make sure that, for the

citizens of this city, life can go on more or less as usual." The

conference would be taking place at the peak of the holiday shopping

season. "The carousel will be up at Westlake, shoppers will fill the

stores, the holiday lights will be up, the PNB [Pacific Northwest

Ballet] will be dancing The Nutcracker. This is still Seattle in

December, after all," wrote the mayor.

Joiner presided over the most exhaustive event planning SPD had ever

done. Almost ten thousand hours of training was provided: over nine

hundred SPD personnel, through the rank of captain, went through an

initial nine-hour "crowd management" (riot control) class. Then weekly,

then twice-weekly squad drills. There were three four-hour

platoon-level exercises and a four-hour session with all platoons

drilling together. There was extra training on the department’s new

chemical agent protective masks, and eight-, sixteen-, and

twenty-four-hour classes on "crisis incident decision making" (a

disciplined approach to analyzing and responding to crises of all

kinds) for supervisors and commanders. Thirty SWAT officers traveled to

Ft. McClellan, Alabama, for a four-day course on WMDs. Several SWAT

supervisors and commanders attended an additional twenty-four hours of

WMD and incident command system training. The Secret Service gave two

days of dignitary protection and escort training to all motorcycle

officers from the five agencies that would be contributing cops to the

cause. The FBI and Secret Service ran two intensive tabletop exercises.

I monitored the training we provided to our officers. It started

with classroom instruction on the short history of the WTO, the protest

methods used in Geneva, and what they could expect, from best- to

worst-case scenarios. Next, the student-officers were herded into an

abandoned hangar at the old Sand Point military facility where they

were subjected—against the audible background of an actual riot (a loud

actual riot, recorded during recent political protests in Vancouver,

B.C.)—to simulated protest strategies and tactics, including violent

attacks. Back and forth the cops went, first as missile-chucking

"demonstrators," then in their real role as frontline cops confronting

those missiles. They rehearsed tactics, prepared mentally for things

likely to come.

All along, I’m thinking, We’ve got this sucker covered.

But my cops? They weren’t so confident. They appreciated the

training, they loved the new equipment—all that all-black "hard gear,"

from catcher-like shin guards to ballistic helmets, making them look

like Darth Vader. But they were convinced the city was in for a real

shitstorm.

There were some ominous signs—Internet organizing and mobilizing,

Ruckus Society training, anarchists threatening to descend on the city

and muck things up not only for the conferees but also for the throngs

of peaceful protesters.

I was familiar with such pre-event refrains from a segment of police

officers who always sound like Chicken Little, as well as the

shut-it-down braggadocio of the lunatic fringe of protesters. I’d heard

the voices of "extremists" many times in my career. Back in the

seventies in San Diego, a wild-eyed lieutenant warned of the day that

fundamentalist religious sects in the Middle East would migrate to our

shores and do bad things to innocent Americans. He prophesied acts of

terrorism, like blowing up airplanes and buildings … if you can

imagine that. The brass labeled him "Ol‘ Bombs and Rockets"—and kept

him away from the armory.

Of course there would be demonstrations downtown. Of course there’d

be knuckleheads who’d try to bait the officers. But even though Seattle

was a small city in a small county in a small state, I was confident my

PD was ready. Joiner had asked for help from state and regional

agencies, and gotten it. From everyone, that is, but Tacoma. Their

chief sent a letter declining to ante up any officers. I tracked him

down at a DV conference. "We really could use your help, James." James:

"We’re shorthanded." Me: "Aren’t we all, aren’t we all. But this thing

could really blow up on us." James: "I’ve got my own city to police."

Me: "But we’re always there for you, James. Sure you won’t change your

mind?" James: "No." Me: "Well, that really blows." James: "But if

things get out of hand up there you can count on us." Thanks, James.

Thanks a bunch. Washington State Patrol, King County Sheriffs, Port of

Seattle, Bellevue PD, Kent PD, and the combined forces of Auburn,

Renton, and Tukwila committed a total of fifty-three motorcycle cops,

seventy-five patrol officers, thirty-one SWAT officers, five bomb cops,

two communications/media personnel, and three explosives-detection K-9

teams. Washington State Patrol and King Country Sheriffs also committed

a total of 145 officers for "demonstration management" duty in the

event they were needed. All of this was to supplement the core forces

of Seattle’s police. On a normal day SPD would field about one hundred

cops at peak times. For the WTO we would have more cops on the streets

than at any time in PD history. In all, nine hundred SPD officers would

be suited up for WTO, all of them working twelve-hour shifts. It sure

sounded like a lot of cops.

Things were moving apace when shortly before the conference, Schell

insisted on visiting roll calls. He wanted to offer words of

encouragement, let the officers know he was there for them—and to tell

them to behave themselves. Maybe he thought they wouldn’t play nice

with our global visitors, that they might not show proper restraint if

provoked. I went with him to the roll calls, stood by his side. The

first few sessions were uneventful, if not dull. The mayor was a

bright, articulate politician but when it came to rallying the cops he

was no Knute Rockne.

The last roll call was at the West Precinct, in a spanking-new

facility, spacious, comfortable, and, unlike so many police facilities,

designed and built with cops and police work in mind. It had that

new-building smell, nice and fresh, and its opening had been a joyous

occasion for the West Precinct cops, mostly because of the pit they

were leaving. And because the plan called for free parking—just like PD

employees at the other precincts enjoyed. But Schell had changed all

that, and the cops were in a foul mood. In fact, they were lying in

wait as we walked in.

There they sat. A roomful of disgruntled cops staring at a

politician who had the nerve to ask them to make a good impression for

the all the world to see, even as he stuck it to them on the parking.

They glared, they griped, they grumbled. When one guy complained about

WTO, hizzoner finally snapped. "Look, if you can’t handle the job I’ll

find someone who can!"

Fighting the urge to throttle the guy, I stepped forward and

reminded the cops of my confidence in them. But the damage had been

done, and the mayor wasn’t through yet. Right after roll call and

within earshot of officers filing out of the room he turned to his

police chief, shook his head and said, "I sure don’t envy you your job."

The next day he said he was sorry. "Tell it to the cops," I said.

"I was tired," he said. "And hungry. I hadn’t eaten since lunch."

Well, sir, neither had I. And the cops you were talking to? They’re

headed for long hours with no sleep, no food, not even a place to pee.

As the conference approached, I began to have some of the same

doubts my officers felt. I took my concerns to Joiner, who brought me

back to reality. The first WTO ministerial conference had been held in

Singapore, which meant, of course, there had been exactly no

demonstrations. And the violence at that second one in Geneva? A

"European phenomenon." Besides, Seattle PD had had a ton of experience

and enjoyed a well-earned reputation for handling big political

protests (while still in San Diego I’d heard positive things about

SPD’s approach to demonstration management). Moreover, Joiner planned

to use only known and trusted SPD personnel at the most sensitive posts.

Ed Joiner had solid credentials as a strategist and tactician. His

planning team included some of the best minds on the department. Plus

every stakeholder, from the regional bus system to local hospitals, was

involved in the planning. Also comforting was the FBI’s threat

assessment of "low to moderate." (I later learned they were talking

about terrorist threats.)

And how’s this for reassurance? The head of the local Secret Service

office told the mayor and me at a meeting in Schell’s office just

moments before kickoff: "If things turn to shit it won’t be for of a

lack of planning." As a matter of fact, he had "never seen a better job

of planning and preparation."

Things started well. There were a couple of small-scale

demonstrations downtown on the Friday before the Monday conference

opening. On Saturday three daredevils rappelled themselves over a

bridge and hung an anti-WTO banner over Interstate 5 (they went to

jail). Sunday there were demonstrations on Capitol Hill, but what else

was new? Later that night a collection of anarchists broke into and

occupied an abandoned building near the West Precinct. Even that wasn’t

all that troubling—it allowed Joiner and his crews to keep an eye on

the comings and goings of the "outside agitators." Further, it would

have been problematic at that late moment to commit the dozens of

personnel necessary to raid the place, scoop up the trespassers, sort

out their undoubtedly counterfeit identities, and jail them—a decision

that was a mistake, in hindsight.

But, it wasn’t a bad weekend. All the more remarkable given that the

conference was gearing up at the same time the city was playing host to

the Seattle Marathon and a Seahawks game—both of which demanded much

from our force.

Early the next morning officers discovered evidence of a possible

break-in at the convention center. They’d been guarding the facility (a

sprawling, multistory building, with a complicated layout, in the heart

of downtown) throughout the night. But as Lt. Robin Clark, our SWAT

commander, showed me, it looked like someone could have slipped through

the outer perimeter, scaled a temporary wall at the back of the

facility, busted open a padlock, and entered the place.

This was serious. Police commanders had not taken as idle the threat

by militant protesters that they would, indeed, "shut down the WTO." It

wasn’t hard to imagine the mess they’d make if they’d breached security

of the main WTO venue. They could set off the fire sprinklers and flood

the interior, spraypaint choice antiglobalization slogans all over the

walls, unleash stink bombs. Or real bombs. Officers had to search the

whole convention center. So they did. Meticulously, with SWAT and

police dogs. It took hours.

The opening ceremonies were delayed, and a few delegates got their

noses bent out of shape—mostly because they got yelled at a good bit by

throngs of raggedy demonstrators as they stood in line in their western

business suits and native attire. One of them, a "minister," pulled a

gun on some demonstrators.

A couple of hours later everyone was safe and snug inside the

building. We breathed a collective sigh of satisfaction, and I returned

to the streets to resume my "roving."

In the Incident Command System, which we had adopted (and trained

for) long before WTO entered the picture, the chief of police has, by

design, no "operational" role. His or her name and title might appear

at the top of official documents, but if you searched those documents

for a job description you’d find none.

There are compelling reasons to keep police chiefs out of the

operations arena. They are simply too busy, across a broad range of

organizational and community duties, to master the kind of continuously

updated specialized expertise needed to handle a SWAT incident, a crime

scene, or a major demonstration.

The last thing you want is a police chief actually running the show. So, I "roved."

I walked the streets, encouraged my cops at their posts, stopped by

the various hotels set aside for WTO delegates and dignitaries, and

moved in and out of the convention center. I spent time with my

commanders in the Multi-Agency Command Center (MACC), the Seattle

Police Operations Center (SPOC) next door, and the Emergency Operations

Center (EOC) at the fire station at Fifth and Battery. (My four

assistant chiefs, with Joiner taking the point, were split between the

MACC and the EOC, each pulling twelve-hour shifts, for around-the-clock

coverage.) I received regular updates and teamed up with the mayor and

the fire chief to make frequent announcements to, and to field

questions from, the huge international press corps. One of my answers

at one of the press conferences would infuriate my cops, but that

wouldn’t come until later.

The first press briefing on Monday was upbeat. I had just come from

an intersection clogged with demonstrators. David Horsey, two-time

Pulitzer Prize-winning political cartoonist with the Seattle

Post-Intelligencer, had been standing next to me as a local protester

approached. She told us she’d traveled downtown for two reasons: to

protest globalization, and to keep people from hurling insults and/or

bottles at her cops. She wanted me to know how much she respected and

admired the job our officers were doing. It was one of those lovely

peace-love-harmony moments. I envisioned the next morning’s political

cartoon, and felt all warm and fuzzy.

Veteran cops told me they’d never seen so many people on the

streets. There was sea of sea turtles and anti-WTO signs, choruses of

chanting, and street theater performances, replete with colorfully

costumed actors on stilts playing out the various points of opposition

to globalization. That night, thousands of protesters filed into Key

Arena where the Sonics and the Storm play their basketball. They heard

speeches from local politicians, including the mayor (who at one point

bleated, "Have fun but please don’t hurt my city") and various protest

leaders and organizers. There were songs by Laura Love and other

politically active musicians. Day One ended peacefully.

Which was in stark contrast to the way Day Two began. Starting at

two in the morning (those protesters needed a union!), demonstrators

began assembling, quietly, but not unobserved (cops do work 24/7).

Throughout the night the MACC and the EOC fielded reports from officers

monitoring the increasing size of the crowds. By five-thirty a large

group had formed at Victor Steinbrueck Park just north of Pike Place

Market. Sprinkled within the crowd were gas masks and chemical

munitions. At seven-thirty large groups began marching to the

convention center from five different locations. Between seven-thirty

and eight o’clock, seven distinct, large-scale disturbances erupted

within a two-block radius. At nine minutes after nine the incident

commander authorized the use of chemical irritants. One minute later he

put out the call for mutual aid.

I stood in the rain at the intersection of Sixth and Union and

witnessed a single line of ten King County Sheriff’s deputies holding

off more than a hundred raucous demonstrators who were trying to

penetrate the underground parking at the Sheraton. The militants

taunted the deputies, pushed up against them. I worried for the thin

tan line, the tiny handful of county cops who rarely saw this kind of

"big-city" action. And realized, for the first time, that we didn’t

have nearly enough cops to get the job done.

Moments later hundreds of demonstrators surged into the middle of

the intersection and took a seat. They completely choked off Sixth

Avenue up to University, a block east. If a police car, a fire truck,

or an aid car had to get to an emergency in or around any of the

high-rise buildings it would have been impossible. Police commanders

had spent months negotiating with protest leaders, but this wasn’t in

the plan. There was no choice but to declare an unlawful assembly and

clear them out. Which wouldn’t be pretty, given what the sitters did

next.

In response to the command to leave the intersection, protesters

locked arms, making themselves one massive knot of humanity. Only force

would unlock them from one another. A field commander told them they

were in violation of the law, and that they would be arrested if they

didn’t leave the intersection. He did it by the numbers: He used the

proper language, stationed cops around the perimeter to verify that the

bullhorned warning could be heard, and warned them and warned them and

warned them. Then he warned them again. Then he gassed them.

Why didn’t he and his squads just wade in, pull the protesters

apart, and haul them off to a prisoner transportation unit? This

particular demonstration wasn’t violent, after all, but a classic civil

disobedience tactic. But there simply weren’t enough cops to pluck them

off one at a time. And violence had broken out at several other

locations around the convention center.

At noon, a scheduled AFL-CIO march left Seattle Center in the shadow

of the Space Needle and headed downtown. It grew from twenty thousand

to forty thousand on the way, and soon converged with another ten

thousand demonstrators already on the streets of downtown. Suddenly, my

minuscule police force seemed microscopic.

Even the reinforcements from other agencies, streaming in and en

route, struck little confidence into the hearts of police staffers. Our

cops were clearly in trouble. The department had co-planned with

organizers from the AFL-CIO and other groups, and had gotten assurances

that they would largely police themselves. These were honorable people

who’d kept their word in the past. One could only hope they’d be able

to hold their own against interlopers.

Those hopes were dashed when even before the tail end of the march

reached downtown, self-described anarchists and Beavis-and-Butthead

recreational rioters unleashed a round of criminal acts.

Thugs in uniform—black with black bandannas—popped out of the

throngs of peaceful protesters and chucked bricks and bottles at cops,

and newspaper racks through shop windows. They even smashed a Starbucks

window and ripped off bags of Arabica, Colombian, and French roast (a

hanging offense in Seattle). Then they scurried back into the crowd

where they cowered behind senior citizens, moms with jogging strollers,

and kids dressed up in those cute little sea turtle costumes.

I walked into a hastily called meeting at the MACC, Joiner’s

windowless headquarters. The mayor was there, so was Washington

governor Gary Locke, Chief Annette Sandberg of the Washington State

Patrol, King County Sheriff Dave Reichert, and a couple of feds who

were in town to do advance work for the president’s visit. Clinton was

due in late that night. The meeting had one item on its agenda: whether

to declare a state of emergency and call in National Guard troops.

Tension in the room was palpable, as you might expect with a city under

siege. But there was also an undercurrent of something else.

The place reeked of fear. It couldn’t have been a fear for our own

safety—we were, for the moment, safely hunkered in and bunkered down,

far away from the din of battle. So what were we afraid of? I can’t

speak for the others, but here’s what I was afraid of: (1) My cops were

out there on the streets, taking a licking; (2) nonviolent protesters,

store owners, office workers, and shoppers faced a clear and present

danger; (3) the president of the United States, leader of the free

world, wouldn’t be able to address the ministers—if he could get in to

the city at all; (4) my beloved city looked more like Beirut, or

Baghdad; and (5) I didn’t know what the hell to do, other than close

down the city and call in the National Guard.

Mostly, I was afraid I’d failed. I had let down a lot of people I

cared about. Sitting next to me in the MACC was Sheriff Reichert who

wanted nothing more than to get back out on the streets to kick some

ass and take some names. Reichert, angry at our insufficiently

"aggressive" plan for dealing with the demonstrators and disgusted by

the dithering in the room, leaned over and whispered, "Let’s just throw

the damn politicians out of the room." I liked the sound of that, but

we needed them: the mayor to put the official request for a declaration

of a "state of emergency" to the governor, the governor to act on it.

Joiner, still in charge in the MACC, remained calm and cool. He held

out for accurate updates from the field. Through his own "shock and

awe" at what had unfolded that day, he was still very much the kind of

operations commander you want calling the shots.

Now, however, everybody wanted to run the show—or at least judge it.

Sandberg sighed audibly, rolled her eyes, and murmured under her

breath when the conversation took a turn she didn’t like. The feds

migrated to a corner of the room, mumbled, crossed their arms, put

their heads together and shook them vigorously. (Paraphrasing, their

position was: Just clear the fucking streets, for God’s sake! We don’t

care what it takes. We got the Big Guy touching down in a matter of

hours. POTUS (the Secret Service abbreviation for "President of the

United States") shouldn’t be exposed to this … this riffraff.) And

Reichert? The poor guy was apoplectic, his blood boiling over every

time Schell opened his mouth.

Those individuals most capable of bringing reason to the table and

advice to the decision makers, like West Precinct captain Jim Pugel,

weren’t in the room. They were, by popular demand, out there on the

streets. Pugel was doing a hell of a job under hellish conditions. He

and other field commanders reported in regularly, but the situation

kept changing, of course, from one minute to the next.

So there we were, a roomful of leaders, accustomed to running

things, taking risks, making decisions, getting things done. As

individuals we made things happen. Now we were suddenly thrust together

as a body, as a team of leaders—though hardly a cohesive one. It

occurred to me that planning and preparation for WTO should have

included at least one tabletop exercise for the "rovers"—the very

people in that room.

At 3:52 the mayor declared a civil emergency. The governor called

out the National Guard. In a script that could have been written by

Joseph Heller, Joiner had asked in advance that the National Guard be

placed on alert. We can’t do that unless a state of emergency exists.

But we’re trying to prevent a "state of emergency." Well, we can’t

mobilize unless a state of emergency exists. Can’t you just have your

people standing by, say, in Kent or SeaTac? Nope. Have your emergency

first, then give us a call. A curfew, which covered most of the

downtown area, was imposed for that evening and the next.

I left the MACC and headed back out on the streets. If anything, the

situation was worse. Police officers were being pelted with an amazing

array of missiles: traffic cones, rocks, jars, bottles, ball bearings,

sticks, golf balls, teargas canisters, chunks of concrete, human urine

shot from high-powered squirt guns. Gas-masked militants fired their

own teargas at the cops, hurled ours back at us, and flung barricades

through plate glass windows. Some moron(s) flattened all four tires on

a herd of parked police cars. By nightfall it was no better. Most of

the action simply moved to Capitol Hill where innocent caf diners got

gassed along with rioters.

But at least POTUS made it in to town safely. At about one-thirty in

the morning he was put to bed at his favorite Seattle hotel, the Westin.

At five o’clock Wednesday morning, having established a "police

perimeter" to keep demonstrators from getting too close to the WTO

venues, officers observed people carrying crowbars, rocks, masonry

hammers, and bipods and tripods (from which to suspend intrepid

activists high in the air, in the middle of intersections). The cops

confiscated what they could and began arresting the first bunch of the

hundreds who would be jailed that day. Against a backdrop of full-scale

urban rioting, police officers and Secret Service agents escorted our

national leader and his entourage from one venue to another—from the

Westin to the Bell Harbor Conference Center on Elliott Bay to the Four

Seasons Hotel. Officers continued to take a pelting but POTUS was never

touched.

By mid-morning the ACLU filed for a temporary restraining order in

U.S. District Court seeking to overturn the "police perimeter." A

police commander had to break away from his duties to summarize the

department’s defense of the tactic, but it paid off. The court denied

the request. (As if the demonstrators were paying any attention at all

to the so-called "no protest zone.")

All that day and into the night, with action shifting once again to

Capitol Hill, cops fought the fight, ducking often as protesters

chucked unopened cans of soup and other objects. A platoon commander’s

car was surrounded by a fun-loving crowd that jumped up and down on the

vehicle, then attempted to flip it over. (The lieutenant, who had

himself been an antiwar demonstrator at the University of Washington

back in the days, told me later, "I’ve been on every kind of call there

is, Chief. But I’ve never been more scared than I was that night. I

thought sure they were going to pull me out of the car, grab my gun,

and … and who knows what.") Officers dispersed that group with gas

and rescued their boss.

Moments later an employee at a gas station on Broadway called 911 to

report that the station had been taken over by rioters who were filling

small bottles with gasoline. One officer witnessed an individual

dressed in black carrying a Molotov cocktail. A crowd of three hundred

to four hundred broke off from the Broadway festivities and moved to

the 1100 block of East Pine where they threatened to take over SPD’s

East Precinct.

At two-fifty Thursday morning the precinct was still under siege,

the crowd having grown to somewhere between a thousand and fifteen

hundred. The officers protecting it were no longer surprised by the

pelting they took, or by the infinite variety of projectiles.

A combination of chemical agents and rubber pellets finally secured

the peace. The building, which contained weapons, injured police

officers, and prisoners, was never breached.

Downtown at dawn was much quieter than it had been the past two

days, a portent of positive things to come. Clinton flew out of town at

ten, and the "no protest" perimeter was shrunk. A crowd circled King

County Jail at about one in the afternoon (triggering a lockdown), but

other than that it was peaceful. Most of the violent demonstrators were

either in jail, lying low, or scurrying out of town. As day turned to

night the crowd continued to hang around the jail, listening to

speeches from protest leaders, criminal defense attorneys, and other

activists. At seven-thirty they split up, half of them sticking around,

the other half, under police escort, heading up to Capitol Hill where

they continued their mostly peaceful ways.

On Friday, the final day of the now-truncated WTO conference, the

drama ended. (If the demonstrators had been shouting "Truncate it!

Truncate it!" instead of "Shut it down!" they would have achieved their

goal.) All that remained of the protests was a hastily negotiated,

legally sanctioned march by organized labor. It drew a decent crowd,

maybe eight hundred to a thousand, but by then the focus had shifted

from the WTO to claims of police brutality and to condemnation of the

curfew and the perimeter. At its conclusion the marchers headed back to

the Labor Temple.

A hundred or so of them broke from the group, marched over to Fifth

Avenue, and swarmed the main entrance to the Westin—did they think

POTUS was still inside? (Protesters earlier in the week had effectively

made hostages of a furious Secretary of State Madeline Albright and

U.S. Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky—both of whom were unable

to leave their hotel rooms for the better part of a day.) Several of

the demonstrators chained themselves to the front door of the hotel. It

was a lame tactic—the Westin had other obvious entrances but there were

too few protesters left to cover those doors. I walked into one of

those other entrances and took the elevator to the twenty-first floor

where a suite had been set up for officers assigned to dignitary

protection at the hotel. I helped myself to a bottled water and walked

over to the window. It was dark outside. A good-size crowd had gathered

to cheer on this last hurrah. We could hear the muffled chants from

behind the thick glass. A couple of hours later, the chains came off

and what was left of the crowd either went home or over to the jail to

shout words of encouragement to their imprisoned brothers and sisters.

The riot was over.

Saturday, December 4. I made one last round of the still-operating

venues, stopping finally at the MACC where I informed the deputy mayor

I that I was turning in my badge.

My decision made headlines. And a Horsey cartoon which had the chief

of police falling on his sword. Its caption: "I figured I’d do it

myself before someone did it for me."

It took great self-discipline for me not to blurt out publicly what

I thought of the mayor. But had I done it, it would not have been for

the things the mayor was being accused of (hubris, navet, lack of

foresight—all of which, if it fit him, also applied to me). In fact, I

strongly believe that Schell got a raw deal for his role in the battle.

It just wasn’t his fault, any of it. The guy wasn’t a cop, or a

tactician, or a "demonstration management" expert. Hell, he’d only been

a politician for two years. But the mayor had acted the fool on other

fronts, and it was those occasions that had riled me. First and

foremost were his reckless remarks to and about Sheriff Reichert.

Riding around at the height of the rioting with King County

Executive Ron Sims, Reichert had observed an act of vandalism. Telling

Sims he’d seen enough, he bailed out of the car and gave chase. He

didn’t catch the suspects, but his actions produced a satisfying sound

bite on the evening news—and endeared him to my cops, who had plenty of

other reasons to favor the county lawman over their own chief.

As the mayor and the sheriff walked out of a hall following one of

Clinton’s speeches, Schell cornered Reichert. He told him he didn’t

appreciate the sheriff "acting like a fucking hero out there," or words

to that effect. He blocked Reichert’s path, and continued to berate

him. The sheriff ignored the mayor, and pushed past him. Schell, always

the gentleman, shouted after him, "I’ll personally destroy you!" The

many witnesses to the mayor’s actions were not impressed.

After the dust had settled, Schell presided over a special cabinet

meeting. He praised all the city departments who’d played any kind of a

role during the week (especially the crews who’d cleaned up around

Westlake Park over the weekend and made downtown sparkle once again).

He thanked us for our personal sacrifices, and so on. It was a gracious

statement. Then he said, "You know, everyone did a terrific job under

incredible stress. Everyone except our lunatic sheriff." Running a Bush

"Mini-Me" campaign—support for the war in Iraq, opposition to

reproductive rights, support for a constitutional amendment banning gay

marriage, opposition to federally funded sex education, support for oil

drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, opposition to

stem-cell research—the "lunatic" won election in November 2004 to the

eighth Congressional District from Washington.

I cornered the deputy mayor after the meeting, Schell having scooted

off. "I’m sick and tired of your boss’s character assassinations." I

told her he was acting like a "narcissistic sociopath," and urged her

to put a muzzle on him.

"I know, I know," she said. "He’s been under such pressure …"

It wasn’t that I didn’t understand. The week had taken a personal

toll on everyone. I, myself, had gone home to my condo in the middle of

the night, four nights in a row with only enough time to shower, air

out my gas-saturated uniform, and try to squeeze in a couple of hours‘

sleep. Bone tired, I found it next to impossible to get to sleep. Some

nights I could still hear the whoop-whoop-whoop of Guardian One, the

sheriff’s helicopter I’d ridden in with the governor in order to get an

eagle’s-eye view of the proceedings. As with a song you can’t get out

of your head, I’d be wracked by a rerun of the day’s other noises:

drums, police whistles, chants, screams, rocks landing on police

helmets and on the face shields of our horses, dueling bullhorns, glass

shattering. I replayed over and over in my mind the frantic radio call

of one of my mounted officers as the cop reported being pulled from his

horse. I’d responded to that one, Code 2, turning onto Pine Street just

in time to catch a faceful of CS gas.

With eyes shut I saw Technicolor images of bipods and tripods,

looters, Dumpster fires, intersection bonfires. I saw cops being baited

and assaulted. And I saw a cop kicking a retreating demonstrator in the

groin before shooting him in the chest with a rubber pellet. That

particular scene, caught by a television camera, was flashed around the

globe, over and over, Rodney King-style.

Then there was the cop who, spotting two women in a car videotaping

the action, ordered one of them to roll down her window. When she

complied, he shouted, "Film this!" and filled their car with mace.

If Paul Schell wasn’t responsible for this mess, who was? I was. The

chief of police. I thought we were ready. We weren’t. I thought protest

leaders would play by the rules. They didn’t. I thought we were smarter

than the anarchists. We weren’t. I thought I’d paid enough attention to

my cops‘ concerns. I hadn’t. All in all, I got snookered. Big time.

To this day I feel the pangs of regret: that my officers had to

spend long hours on the streets with inadequate rest, sleep, pee

breaks, and meals, absorbing every form of threat and abuse imaginable

(including, for a number of officers, a dose of food poisoning, from

eating vittles that had been sitting out all day); that Seattle’s

businesses were hurt during the rampaging; that the city and the police

department I loved lost a big chunk of collective pride and

self-confidence; that peaceful protestors failed to win an adequate

hearing of their important antiglobalization message; and, yes, that

Paul Schell’s dream of a citywide "dialogue" had been crushed.

When I think back to that week in 1999, which I do probably too

often, one event stands out. It’s three in the morning. I’ve just

walked into my darkened condo on Lower Queen Anne.

I check for phone messages. There’s only one. I’m sure it’s from one

of my cops. Friendly and jovial on Day One, the officers had joked with

me, shown off their new equipment, passed along compliments they’d

heard from protesters. But this was Day Three, and now they were

shooting me nasty looks. Why?

Word had spread through the ranks that I’d answered "yes" to a

reporter who wanted to know if I’d seen any police conduct that

disturbed me. Well, I sure as hell had, and I wasn’t about to lie about

it. That I’d lavishly praised the sterling performance of my officers

at a string of press conferences made no difference to many of my cops.

I’d broken an important provision of "the Code." Like the Republicans‘

"Eleventh Amendment," police officers are not to speak ill of one

another—even if one of them has assaulted an unarmed, retreating

demonstrator. Or maced innocent women. In neither of these incidents

was a Seattle police officer involved. The "kicker-shooter" belonged to

Tukwila PD, the "macer" was Reichert’s. Both agencies responded

immediately, taking their cops off the streets—and later imposing stiff

penalties.

I punch in the code and retrieve the message. It’s not from a cop,

after all. It’s from a friend. A doctor friend I have dinner with

several times a year. I sigh. Thank God, I can use a little support

right about now.

"I can’t believe what I’m seeing on TV," says the friend’s voice,

dripping with venom. "Your cops are worse than the fucking Gestapo. I’m

totally repulsed that you’re allowing this. You’re a sorry, miserable

excuse of a human being and I’m appalled that you’re our chief."

But at the end of the week there was this: My cops hadn’t killed

anyone. Given fatigue, provocation, and ample legal justification to

employ lethal force on numerous occasions, they’d held their fire. The

Battle produced not a single death (and fewer than a hundred injuries,

the most serious of which was a broken arm).

The Battle of Seattle was an important event in the history of

American social and political protest. Whereas ten years ago a thousand

people might have shown up to protest the WTO, there were fifty times

that number on the streets of Seattle in the fall of ’99. I believe

that’s a testament not only to the power of the Internet (which has all

but replaced posters on fences, campus leafleting, and telephone trees

as the primary means of organizing and mobilizing protest) but also to

broad, intense antiglobalization sentiment and to a deep mistrust of

our government’s policies. Witness the awesome numbers of protesters

who took to the streets locally (as well as globally) to protest

America’s invasion and occupation of Iraq.

Seattle was, in the end, just too damned small to pull it off. If

you’re thinking about hosting such an event you need to be able to

count your cops in the thousands or tens of thousands, not hundreds.

Hell, the city wouldn’t have had enough cops had we called in every

officer in the state.

We learned many lessons from the Battle, foremost of which are: (1)

line up as much help in advance as you possibly can, then find more;

(2) plan for "force multipliers" (i.e., volunteers), but don’t become

overreliant on them; and (3) keep demonstrators at a much greater

distance from official venues. No matter how much they bitch about it.

And finally, my gift to every police executive and mayor in cities

the size of Seattle’s: Think twice before saying yes to an organization

whose title contains any of the following words: world, worldwide,

global, international, multinational, bilateral, trilateral,

multilateral, economic, monetary, fiscal, finance, financial, fund,

bank, banking, or trade.